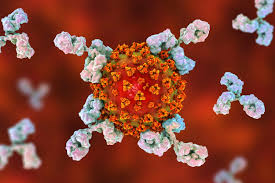

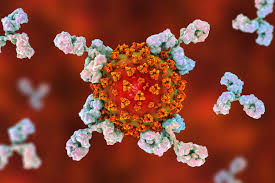

A new research on Covid-19 that shows that antibodies within a human fall rapidly after recovering from the disease has dampened hopes that entire populations can become immune to the disease.

Some scientists had proposed the so-called herd immunity developing against the disease and that was touted as a better chance of eliminating the pandemic compared to lockdowns. However achieving herd immunity would require that about 50 per cent to 60 per cent of the total population being able to develop a natural protection against the virus so that further human to human transmission cannot be done by the virus efficiently.

However according to the findings of a recent and major study in the United Kingdom, instead of being able to build immunity over time, there was a drop of 26 per cent in the number of people with antibodies since the easing of the lockdown during summer.

365,000 people over three rounds of testing between June and September were screened by researchers from Imperial College London.

About 6 per cent of the people had antibodies to the virus at about the time period when the government had started to ease lockdown measures in late June and early July, shoed results of the REACT-2 study.

But that dropped to just 4.4 per cent by the start of the second wave last month.

The new results strongly suggest that herd immunity is unachievable, said professor Helen Ward, one of the researchers.

"When you think 95 people out of 100 are still likely to be susceptible, we are a long, long way from anything resembling population level protection against onward transmission," she said.

"It's not something you can use as a strategy for infection control [for COVID-19] in the population."

According to the controversial Great Barrington Declaration, it should be possible to build up herd immunity by shielding the vulnerable people at home while the virus spreads through the young and healthy population. That notion has been now been shattered according to this new research.

Higher antibody levels were found to be present among younger people from black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities and health workers, the study found, potentially because of such people being in regular contact with infected people.

The results of this study shows that regular re-infection of Covid-19 will happen just as it happens for other coronavirus that causes common cold.

Presence of antibodies peak in about three to four weeks after symptoms arises and then drops away just like other of the related viruses, said professor Wendy Barclay, an infectious diseases specialist and one of the researchers.

"Seasonal coronaviruses that circulate every winter and cause common colds can re-infect people after six to 12 months. We suspect that the way the body reacts to infection with this new coronavirus is similar to that," she said.

But only a handful of documented cases of re-infection have so far been found.

"What is not clear is how quickly antibody levels would rise again if a person encounters the virus a second time. It is possible they will still rapidly respond, and either have a milder illness, or remain protected through immune memory. So even if the rapid antibody test is no longer positive, the person may still be protected from re-infection," said Dr Alexander Edwards, associate professor in biomedical technology at the University of Reading.

(Source:www.skynews.com)

Some scientists had proposed the so-called herd immunity developing against the disease and that was touted as a better chance of eliminating the pandemic compared to lockdowns. However achieving herd immunity would require that about 50 per cent to 60 per cent of the total population being able to develop a natural protection against the virus so that further human to human transmission cannot be done by the virus efficiently.

However according to the findings of a recent and major study in the United Kingdom, instead of being able to build immunity over time, there was a drop of 26 per cent in the number of people with antibodies since the easing of the lockdown during summer.

365,000 people over three rounds of testing between June and September were screened by researchers from Imperial College London.

About 6 per cent of the people had antibodies to the virus at about the time period when the government had started to ease lockdown measures in late June and early July, shoed results of the REACT-2 study.

But that dropped to just 4.4 per cent by the start of the second wave last month.

The new results strongly suggest that herd immunity is unachievable, said professor Helen Ward, one of the researchers.

"When you think 95 people out of 100 are still likely to be susceptible, we are a long, long way from anything resembling population level protection against onward transmission," she said.

"It's not something you can use as a strategy for infection control [for COVID-19] in the population."

According to the controversial Great Barrington Declaration, it should be possible to build up herd immunity by shielding the vulnerable people at home while the virus spreads through the young and healthy population. That notion has been now been shattered according to this new research.

Higher antibody levels were found to be present among younger people from black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities and health workers, the study found, potentially because of such people being in regular contact with infected people.

The results of this study shows that regular re-infection of Covid-19 will happen just as it happens for other coronavirus that causes common cold.

Presence of antibodies peak in about three to four weeks after symptoms arises and then drops away just like other of the related viruses, said professor Wendy Barclay, an infectious diseases specialist and one of the researchers.

"Seasonal coronaviruses that circulate every winter and cause common colds can re-infect people after six to 12 months. We suspect that the way the body reacts to infection with this new coronavirus is similar to that," she said.

But only a handful of documented cases of re-infection have so far been found.

"What is not clear is how quickly antibody levels would rise again if a person encounters the virus a second time. It is possible they will still rapidly respond, and either have a milder illness, or remain protected through immune memory. So even if the rapid antibody test is no longer positive, the person may still be protected from re-infection," said Dr Alexander Edwards, associate professor in biomedical technology at the University of Reading.

(Source:www.skynews.com)