For the first time ever, analyzing the special red light from space, astronomers have spotted a planet in the act of formation.

There is still much that scientists don’t know about how planets like those in our Solar System were first made, despite all that has been discovered about the basics of planet formation.

While locating a planet in its process of formation – often referred to as a protoplanet, a world in the process of being born, has been a goal of astronomers for some time, the faint light given out by a growing planet has made them difficult to spot.

In what is being called the first world formation ever seen in action, scientists have located a planet named LkCa 15b, which orbits a star 450 light years away, is on its way to becoming a planet similar to our system’s Jupiter.

“I was pretty excited as soon as I processed the data, but I wanted to be cautious,” said Kate Follette, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford and co-lead author.

“I was pretty sure I had found something interesting, but in this field we’re always chasing objects that are just at the edge of what we can detect. The really cool thing is that it survived all of our tests to make sure it was real,” Follette said.

By chasing the light of a particular signature predicted by planet formation theory, Follette and her colleagues were able to produce a digital picture of this alien world growing in the light of ultra-hot hydrogen gas.

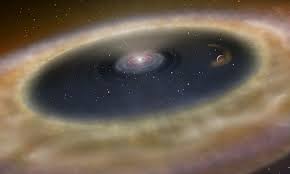

A transition disc – a ring of dust and rocky debris orbiting a sun is the basic ingredient for planet formation is what astronomy theory says. While leaving central clearings in the disc, this debris is swept together to form first the core and then the rest of the planet. But finding these gaps was no easy task.

The falling of hydrogen gas into the core of the protoplanet creates a characteristic wavelength of light after it is heated up and glows. This emits a wavelength of visible light called H-alpha and this is what Follette’s team decided to chase.

The University of Arizona's Magellan Telescope in Chile was used by the team was which was able to find this shade of red light emanating from LkCa 15b as it formed. The light shade was visible despite being born close to the much brighter light of its sun.

“The difference in brightness between a star and a young exoplanet is usually comparable to the difference between a firefly and a lighthouse,” Follette said.

“It’s very hard to isolate the light from the planet when it is so faint and so close to the star from our point of view. But, because we could focus on a special colour of light where the planet is glowing very brightly, the signal was significantly stronger than what we normally look for,” Follette said.

The Magellan’s visible light camera using adaptive optics system is capable of imaging at H-alpha and this was the reason that the process was possible. The adaptive optics system corrects for the bending of light as it passes through Earth’s atmosphere.

(Source:www.forbes.com)

There is still much that scientists don’t know about how planets like those in our Solar System were first made, despite all that has been discovered about the basics of planet formation.

While locating a planet in its process of formation – often referred to as a protoplanet, a world in the process of being born, has been a goal of astronomers for some time, the faint light given out by a growing planet has made them difficult to spot.

In what is being called the first world formation ever seen in action, scientists have located a planet named LkCa 15b, which orbits a star 450 light years away, is on its way to becoming a planet similar to our system’s Jupiter.

“I was pretty excited as soon as I processed the data, but I wanted to be cautious,” said Kate Follette, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford and co-lead author.

“I was pretty sure I had found something interesting, but in this field we’re always chasing objects that are just at the edge of what we can detect. The really cool thing is that it survived all of our tests to make sure it was real,” Follette said.

By chasing the light of a particular signature predicted by planet formation theory, Follette and her colleagues were able to produce a digital picture of this alien world growing in the light of ultra-hot hydrogen gas.

A transition disc – a ring of dust and rocky debris orbiting a sun is the basic ingredient for planet formation is what astronomy theory says. While leaving central clearings in the disc, this debris is swept together to form first the core and then the rest of the planet. But finding these gaps was no easy task.

The falling of hydrogen gas into the core of the protoplanet creates a characteristic wavelength of light after it is heated up and glows. This emits a wavelength of visible light called H-alpha and this is what Follette’s team decided to chase.

The University of Arizona's Magellan Telescope in Chile was used by the team was which was able to find this shade of red light emanating from LkCa 15b as it formed. The light shade was visible despite being born close to the much brighter light of its sun.

“The difference in brightness between a star and a young exoplanet is usually comparable to the difference between a firefly and a lighthouse,” Follette said.

“It’s very hard to isolate the light from the planet when it is so faint and so close to the star from our point of view. But, because we could focus on a special colour of light where the planet is glowing very brightly, the signal was significantly stronger than what we normally look for,” Follette said.

The Magellan’s visible light camera using adaptive optics system is capable of imaging at H-alpha and this was the reason that the process was possible. The adaptive optics system corrects for the bending of light as it passes through Earth’s atmosphere.

(Source:www.forbes.com)